South Africa

Family Literacy Project

Country Profile

Population: 47 432 000 (2005 UIS)

Population living on less than 2 US$ a day: 34 % (2005 UIS)

Context

In South Africa it is estimated that between 7.4 and 8.5 million adults are functionally illiterate and that between 2.9 to 4.2 million people did not go to school at all. One million children in South Africa live in a household where no adult can read. In a recent survey, it was found that just over 50% of South African families own no books for recreational or leisure time reading. It is perhaps not very surprising, given this information, that in 2003 a national evaluation by the Department of Education found that the average Reading Comprehension and Writing score for Grade 3 children was only 39%.

The Family Literacy Project (FLP) is based in the southern Drakensberg area of KwaZulu-Natal with a population of 300,000. The unemployment rate currently stands at 41% and 66% of households live on less than R800 per month. The majority of people do not have access to electricity or proper sanitation and this has serious consequences in an area where it is estimated that 30% of the population is HIV positive.

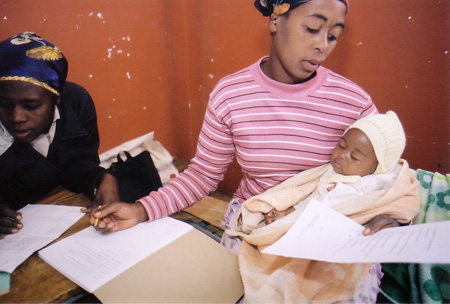

The project is aimed at families as a means of addressing the low literacy achievement of many pre- and primary school children, and the lack of confidence of parents in their ability to provide support to these children. As the parents (or those who take on the role of parents) are the first and most important educators of children, the Family Literacy approach supports both adults and children.

Programme

The FLP was set up in 2000 in response to findings that showed that the literacy scores of pre-school children were not improving, despite government interventions in the early childhood sector. Initially, monthly meetings were held with the parents of pre-school children to work with them to strengthen their role in early literacy development. By the end of that year, the parents were more confident in their ability to support their children whatever their own levels of literacy. These parents, and others in the area, requested that the FLP provide adult literacy tuition. Each group chose a member of their community to take part in training organised by the FLP. These women have since been trained in adult literacy (mother tongue and English as a second language), early literacy, and the participatory Reflect approach. Participation by the group members is important as the FLP believes that local knowledge is significant and relevant and that any new information must be integrated into this knowledge.

The FLP approach now combines these three aspects and eleven facilitators work directly with 197 adults, 479 primary school children and 116 teenagers to achieve the aims of:

- making literacy a shared pleasure and a valuable skill within families;

- helping to develop a critical mass of community members of all ages who see literacy as important and enjoyable;

- supporting parents/caregivers in their role as the educators of young children.

The adult groups focus on building literacy skills, sharing local knowledge and introducing new information where necessary. Topics covered in the groups range from children’s rights and protection to women’s health, environmental issues, and committee and budgeting skills. The adult groups regularly discuss issues relating to children, consider how to support their development, and have fun with them as they look at or read books together.

The FLP stresses the importance of the parent/caregiver as the first educator of children, and the adults in the project are supported in this role. In turn, a number of group members visit their neighbours as part of the project’s home visiting scheme. The 69 home visitors share information on, for example, how to play with children and take care of their health. This innovation has resulted in additional training for group members to help promote early literacy development and health in a playful, interactive way with both adults and children in their homes.

The main barrier to the smooth running of group sessions is posed by the members’ workload. Women will miss sessions when they have to cut thatching grass, re-thatch their homes, or rebuild/plaster walls. If a government-funded initiative requires short-term workers, FLP group members are often the first to apply and as a result will then be absent from the sessions for the duration of the contract. Another challenge is the state of the roads in this very rural area. The roads are bad even when the weather is good and when it rains or snows they are often impassable, which disrupts the support the project offers by visiting each facilitator once a month.

The groups made up of teenage and primary school children explore many issues and relate these to the enjoyment of books and reading. Often, the topics will be the same as those covered in the adult groups, providing opportunities for families to discuss these issues together in their homes.

The problem of low literacy levels in adults and children is exacerbated by the lack of books in the area. To address this, the project established three community libraries and eight box libraries which are run by project facilitators with the assistance of group members.

In addition, project staff have developed learning materials and easy to read books that are available in both Zulu and English. The topics covered in these books include early literacy development, parenting, HIV/AIDS, and resilience. The facilitators are provided with all units (lesson plans), as well as posters and leaflets where these are appropriate and available. The project supplies stationery for the adult, teenage and children’s groups. Group members do not have to leave the project until they want to, as there is no defined end to the programme.

All the facilitators and group members are from the community in which the groups operate. The age range of the group members, who are all women, is between 21 to79, with the average age being forty-eight.

Lessons learned

The most important lesson learned has been that children who are supported by their parents usually do well at school, and that this motivates adults to continue offering this support. The FLP has also learned that well-supported facilitators are key to the successful implementation of the programme.

The FLP must maintain the focus on families as new members join the project. The first members, many of whom are still in the project, joined because they were interested in learning more about how they could help their young children and at the same time develop their own literacy skills. It is important that women who now join this well established and recognised project realise and subscribe to its core mission and vision.

Danisile Gladys Duma (b.1948) has been a regular member since the first family literacy meetings held in Lotheni. In 2003 she wrote (in Zulu):

“I was born in kwaNoguqa and grew up in Mpendle. I started school and went as far as Std 2. I stopped schooling because my home had nothing. I stayed at home, although I desired to learn, but I had to look after cattle.

I was married when I was 15 years old … during the ninth year (of marriage), I had a baby girl …. She is the only child I have. My child grew up and went to school. I had wished that my child should be educated and not have to go through a similar experience to me, as I had a very sad experience because I was not educated.

In 2001, an adult school was established, and I joined it. Now my life is interesting, and I am free. I thank this adult school.”

The Family Literacy Project knows that if literacy skills are not regularly used they can be difficult to maintain. For this reason, group members are encouraged to contribute to the project newsletter, have pen friends, write for community notice boards and keep journals with their children.

Group sessions for adults are advertised by word of mouth and are open to all. FLP experiences low drop-out rates and when members are absent they send apologies and give reasons. It is clear that members are motivated to remain in the programme (the average is 3.5 years for the groups running since 2000) because they are treated with respect and the programme is relevant to them and to their families.

Family literacy can be developed in different ways and can benefit both adults and children. The FLP experience has shown that combining adult and early literacy in a participatory manner can work. It is for this reason that the staff of the FLP have been meeting with other organisations and government departments to explore how to offer family literacy in a way most appropriate in the different contexts. To do this, FLP draws on its experience and shares the lessons learned with others. The women who joined the project in the first years have now become not only competent facilitators but are also able to speak at meetings and conferences and lead training courses outside their own area. Their confidence has grown and the main challenge now is how they are going to meet the different demands on their time.

The project has been evaluated every year and the latest reports are available on the FLP website. The recommendations from the evaluations are taken seriously and followed up each year by the external evaluator. Different evaluation approaches have been used, including storytelling, photographs and stories, focus groups, interviews, and group members reflecting on their own practice.

As NGO work is dependent largely on donor funding, donors who change their priorities can pose a real challenge to the NGO because it then has to source new donors. For example, FLP’s 2007 budget is close to R2,000,000, but it is not possible to extract the cost per learner from this total, as the very small staff of 2 full time and 11 part-timers are involved not only with group work but also materials development, outreach, fundraising and management. In addition, the project contracts a health expert and external evaluators and these costs are included in the overall budget. As donors do not make long-term commitments and some do not let organizations know well in advance when they are going to change their funding criteria, this poses a major challenge to the FLP. Meantime, as many people – convinced of the importance of the inter-generational transfer of knowledge, skills and support – are working to raise the profile of family literacy in South Africa, as in many other countries, it is possible that resources, whether financial and technical will be forthcoming.

Contact

Snoeks Desmond

Director: Family Literacy Project

3 Achadhu

337 Montpelier Road

Durban 4001

South Africa

Snoeks@global.co.za

Lynn Stefano

Project Development Manager

Family Literacy Project

Box 441

Hillcrest 3650

KwaZulu-Natal

South Africa

stefanola@telkomsa.net

www.familyliteracyproject.co.za

Homepage

Homepage