Uganda

Family Basic Education (FABE)

Literacy and Adult Education (LABE)

Country Profile

Population: 28 816 000 (2005)

Population below national poverty line: 37.7 % (1990-2003)

Context

As a result of government efforts to achieve universal primary enrolment, 7.3 million children throughout most of rural Uganda have become literate. However, most adults are still illiterate. Despite the government Functional Adult Literacy Programmeme (FAL), only about 10% of would-be adult learners are reached.

The Uganda Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) targets households, assuming that families will demand and claim access to quality basic social services. Yet information on available services is in printed form and claiming these rights requires mastery of literacy and numeracy - skills which family members do not necessarily have.

FABE (Family Basic Education) is a programme set up by LABE (Literacy and Adult Basic Education), a leading NGO in the field of basic education. LABE first became interested in the possibility of family education projects in the mid nineties as a new dimension of its adult literacy work in the rural regions, and piloted the programme in Bugiri district of Eastern Uganda in 2000-2001. By 2005 the programme was active in 18 schools, reaching over 1400 parents and over 3300 children.

As parents further realised the value of literacy, they wanted to support their children in their school work but felt increasingly inadequate. In response to this felt need and the community education plans initiated by local school management committees, concerned parents and local government and district education officials, LABE negotiated a project with Comic Relief through Education Action International to expand the coverage of the pilot project.

Expanded Programme

The project targets families in Bugiri district, which is one of the poorest districts in Uganda. Its primary schools perform well below the national average and its adult literacy rates are among the worst in the country, especially for women. The programme works with teachers and adult educators whose capacities are built on family literacy methods.

Aside from literacy and numeracy, the programme also aims to:

- Strengthen parental support for children’s educational needs and equip parents with basic knowledge on school learning methods;

- Increase parents’ inter-communication skills while interacting with children and their teachers;

- Develop parenting skills;

- Create awareness on family learning; and

- Enrich the abilities of teachers and adult educators in child-adult teaching/learning methods.

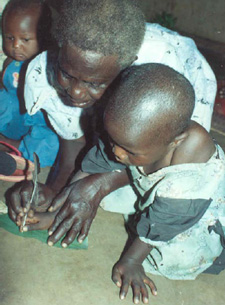

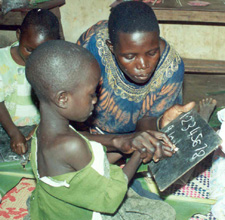

Consequently, the adult basic literacy and numeracy sessions for parents only and joint parent-child sessions are structured towards building shared learning and promoting home learning activities which complement school learning.

The adult literacy sessions are partly based mainly on the school curriculum but structured differently for adult learners. Joint parent-child learning sessions include activities such as playing games, and telling and writing stories together.

Home learning activities use stories, folklore and other activities to extend school learning to the home.

‘Favourable education practices’ must also be established to encourage a link between school learning and community indigenous knowledge, practices and cultural heritage and involve various stakeholders in the planning, implementation, monitoring and shaping of what goes on at school. It is also important to transform ‘ordinary’ events or facilities such as class visits, school open days, school compounds into effective learning opportunities. Finally, home visits are organised to help parents to create both learning space at home and homemade teaching/learning materials.

Each participating school receives a package of materials, while parents make low-cost, home-made teaching/learning materials, either on their own or in the joint parent-child sessions. FABE has developed a teacher’s guide for adult educators and teachers and introduced various participatory techniques to complement teachers’ existing materials.

The approach combines the use of professional teachers (primary school teachers) and para-professional adult educators (adult literacy educators). English and Lusoga (local language) are the medium of instruction.

Lessons learned

One of the challenges was to enable parents (especially mothers) and children (especially girls) to play an active but informed role in community affairs, using the school as an entry point. As the programme progressed, diverse empowerment results emerged, some of which were initially unknown or unintended.

Parents were now consciously interacting with children to reinforce reading, writing and numeracy skills. They were helping children with homework and checking their children’s books. Some parents were even gathering local learning materials for children, such as bottle tops and counting sticks.

They increasingly engaged with their children´s education, sending written notes to school teachers concerning their children’s learning progress or the challenges they faced. They also attended school activities, such as meetings and open days, and visited the school informally to talk to their children’s teachers about their educational progress.

As for the parents themselves, after more than 2 years of FABE literacy-related work, they are able to: 1) correctly read sequences of numbers from 0 to 1,000 and calculate three-digit numbers in writing; 2) record in writing short messages heard on the radio and copy details from a calendar, notice or other text.

Some of these changes were unexpected. To be able to make broad generalisa-tions and use these results for policy recommendations, it was necessary to obtain larger sample sizes and subject the results to greater quantitative analysis. Using control groups from neighbouring schools where no FABE activities were carried out, the following results have been recorded:

Family level (household level)

- Number of children reporting domestic violence (especially slaps from their fathers) has dropped by 15%.

- Number of young girls married off (before they are 15) has dropped by 40%.

- Number of women presenting themselves for election in school, church and village committees has increased by 65%.

School level

- Increase in girls’ overall school attendance has increased by 67 days each year.

- Drop-out rate of girls has decreased by 15%.

- Number of women in school governance structures has increased by 68%.

- Number of parents who take part in developing School Development Plans has increased by 65%.

Community level

- Number of (previously non-literate) community members who took part in the last national elections by independently selecting a candidate of their choice has increased by 27%.

- Ratio of new community members who have joined local voluntary associations has risen to 3:5 (3 being the new members).

In addition to the improved reading, writing and numeracy results, FABE has also produced broader social, economic and political effects:

- Increased resource allocation by local governments to adult learning.

- Increased donor interest.

- Community and parental involvement in basic education now a government policy priority (though the emphasis is still on children’s literacy).

In the future, FABE would like to achieve the following:

- Expand the content of family learning but emphasise literacy and contextualised basic education in a broad sense;

- Present convincing evidence of the complementarity of basic education for children and adults;

- Diversify but at the same time retain the coherence and clarity of what constitutes family basic education in an African setting. Avoid getting sidetracked by divergent interpretations and terminologies;

- Develop an assessment framework for basic adult education competencies that can equally be used to assess the qualifications system for basic children’s education; and

- Market FABE further to gain the support of local and central governments and win funders for sector-wide support – not an NGO project approach.

Contact:

Patrick Kiirya

kiiryadelba@gmail.com

Website: www.labeuganda.org

Homepage

Homepage