India

Reading for a Billion: Same Language Subtitling on TV

Planet Read

Country Profile

Population: 1 103 371 000 (2005)

Population below national poverty line: 29 % (1999)

Internet users per 1000 inhabitants: 16 (2002)

Proportion of households with a TV-set: 32 % (2002)

Proportion of households with a Radio receiver: 35 % (2002)

Context

According to the 2001 Census, India’s literacy rate at that time was 65.4%. Officially, the population aged seven and above consisted of 562 million literates and 296 million non-literates. But what does a literacy rate of 65.4% actually mean? Can 65.4% of the 7+ population “read and write with understanding,” at least simple passages? Clearly not. It is well-known that a large proportion is actually “early-literate”. This refers to individuals classified as “literate” in the census, but who cannot, for instance, read and make meaning of a simple passage in a newspaper. Based on our own research, we estimate that 25% of the population is actually functionally literate (or better) and 40% is early-literate. In numbers, India has at least 350 million early-literates, half of them living in the Hindi speaking states but also large numbers in the Andhra Pradesh and Orissa states.

Although national policies are quick to label people “literate”, the resources channeled towards enabling illiterate people to make the transition to “literacy,” succeed, at best, in helping them to achieve early-literacy. However, the challenge is to keep the early-literate sufficiently motivated and engaged in activities that could, in effect, ensure lifelong engagement with the written word. There is enormous skill erosion, relapse and inefficient use of resources because many early-literates never achieve functional reading levels. The promotion of lifelong reading, beyond the stage of early-literacy, is a necessary component of any long-term solution for illiteracy.

Programme

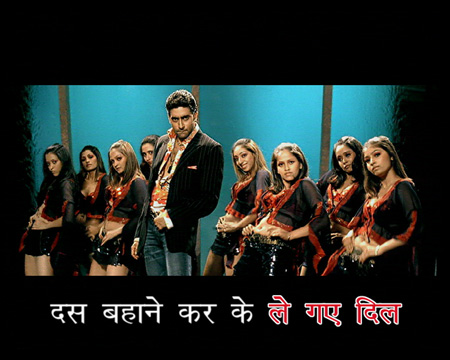

Same Language Subtitling (SLS) is a simple idea that consists of subtitling music videos and film songs on television, in the “same” language as that used for the audio track. What you hear is what you read, with every written word highlighted in perfect timing with the audio track.

The SLS innovation is an example of how existing elements, previously used for purposes unrelated to literacy, were combined to produce a powerful tool for the promotion of mass, lifelong reading. Prior to 1996, when SLS was first proposed, subtitling was primarily used for translation, closed-captioning for the hearing impaired and karaoke for private or semi-private entertainment among literates who could afford it. Television served mass entertainment, information and news. Bollywood, essentially,, entertained. The SLS project expressly combined these elements to provide reading practice opportunities on people’s screens at home. People were not expected to change their habits, yet overnight, reading became an automatic and subconscious part of mass entertainment.

“SLS had a serendipitous beginning. In 1996, while completing my doctoral dissertation in education at Cornell University, some of us were watching a Spanish film, with English subtitles. Being students of Spanish, I commented ‘If only they had put Spanish subtitles to simply mirror the dialogue, we’d learn so much more Spanish!’ And then I followed up with another casual comment, ‘If they just put Hindi subtitles on Hindi film songs, India might become literate!’ Six months later, I had the opportunity to turn this idea into a research project, when I joined the faculty of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad.”

Brij Kothari, President, PlanetRead

Group singing from lyrics written down from TV

From 1996 to 1997, extensive feedback was obtained from people in villages, railway stations, bus-stops and slums to understand whether people preferred to watch Bollywood songs with or without SLS. It was clear from the beginning that viewers liked songs with SLS better, mainly because it allowed them to sing along and learn the song lyrics. This was followed in 1998 by an experimental study conducted with low-income primary school children, during which exposure to SLS was strictly controlled. On average, the reading skills of subjects exposed to regular SLS viewing – three sessions a week for 30 minutes/session over three months – improved more than those of subjects with no exposure to SLS.

By 1999, SLS was implemented for the first time on Gujarat state TV. SLS was added to a popular weekly 30-minute programme of Gujarati film songs. After six months of SLS on state TV, the reading skills of the group exposed regularly to SLS improved more than those of a control group of non-SLS viewers. In 2002-2003, the SLS project won a grant from Development Marketplace (World Bank), making it possible to implement SLS on ‘Chitrahaar’, a programme of Hindi film songs broadcast across the country. Using a random sample of 13,000 people from four Hindi speaking states and Gujarat, we set a baseline of reading skills in 2002. A first impact study was conducted a year later, using the same sample population and test procedures.

Since 2003, SLS has been implemented on ‘Rangoli’, another programme of Hindi film songs that is broadcast nationwide. From January 2006 to May 2007, SLS was implemented on 10 TV programmes in the same number of languages, with the support of the Google Foundation. A second large-scale impact study was conducted in April 2007, nearly five years after SLS in Hindi was first launched on national TV.

Lessons learned

SLS contributes significantly and measurably towards improving reading skills among adults and children.

SLS essentially:

- more than halves the percentage of school-going children who will still not be able to read after 5 years of schooling;

- doubles the percentage of school-going children who will become functional readers;

- halves the percentage of adults and children experiencing reading skill loss and substantially increases the percentage of people experiencing skill gain; and

- leads to 25-30% more people reading newspapers.

In addition, SLS boosts programme ratings (and popularity) by 10-15%.

It costs around $20,000 per year to subtitle one weekly TV programme lasting 30 minutes. SLS currently has an annual budget of$200,000, which it uses to provide nearly 200 million early-literates with weekly reading practice in 10 Indian languages.The average cost per person per year is $US 0.001. In other words, every dollar invested in SLS provides reading practice to 1000 people per year in India.

The antenna that brings reading to 600 000 villages

Learner motivation to read along with the songs is inherent in people’s passion for Bollywood songs and their interest in learning the lyrics. Research has proven that if SLS is available, it will be read by anyone who has acquired at least some early alphabetic skills. Learner frustration among the early-literate does not build up easily while reading along with songs. The “answer” to what they are not able to read fast enough is always provided by the audio track or, if they know the song, by their own memory. Thus, SLS for songs allows struggling readers to experience moments of success, regularly, in the course of their reading experience.

Although the funding needs of SLS are miniscule compared to what it achieves on a national scale, SLS has not yet succeeded in making the transition from project to policy. While it has received short-term funding from the World Bank, Google Foundation, and the Govt. of India, this has not yet developed into a steady source of funding. As a consequence, the project itself has always tended to have a horizon of not more than one year.

The SLS project needs to win over the minds of policy-makers and leaders in national agencies working for literacy. Despite strong evidence from independent research and our own studies, many find it hard to accept that a high level of literacy can be derived from such an apparently insignificant change.

On the policy front in India, the Broadcasting Corporation of India (Prasar Bharati) and the State Broadcaster (Doordarshan) have shown enormous interest in scaling up their SLS service in all languages. A major challenge is the establishment of a sustainable source of support, preferably from the government through the Department of Education. And until this support is provided, SLS will continue to depend on funds from foundations and the corporate sector.

SLS can also contribute significantly to lifelong reading development in other countries – wherever music videos are popular on TV and reading skills are low. PlanetRead was created in 2004 to spearhead SLS in other countries, especially in Africa and South Asia (Kothari, 2007).

Contact:

Brij Kothari

President of Planet Read

26 Manor Drive,

Piedmont

CA 94611

USA

www.planetread.org

brij@planteread.org

References

Kothari, Brij (1998). Film Songs as Continuing Education: Same Language Subtitling for Literacy. In: Economic and Political Weekly, 33(39):2507-2510 (Sept. 26, 98).

Kothari, Brij, Avinash Pandey, and Amita Chudgar (2004). Reading Out of the “Idiot Box”: Same-Language Subtitling on Television in India. In: Information Technologies and International Development, vol. 2(1): 23-44.

Kothari, Brij, Joe Takeda, Ashok Joshi, and Avinash Pandey (2002). Same Language Subtitling: A Butterfly for Literacy? In: International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21(1): 55-66.

Kothari, Brij, Tathagata Bandyopadhyay, Vinod Ahuja and Debanjan Bhattacharjee (2007). Same Language Subtitling on TV: Impact on Basic Reading Development among Children and Adults. Unpublished report.

Kothari, Brij (2007). Same Language Subtitling on TV in Africa: A Concept Note (available upon request).

Homepage

Homepage